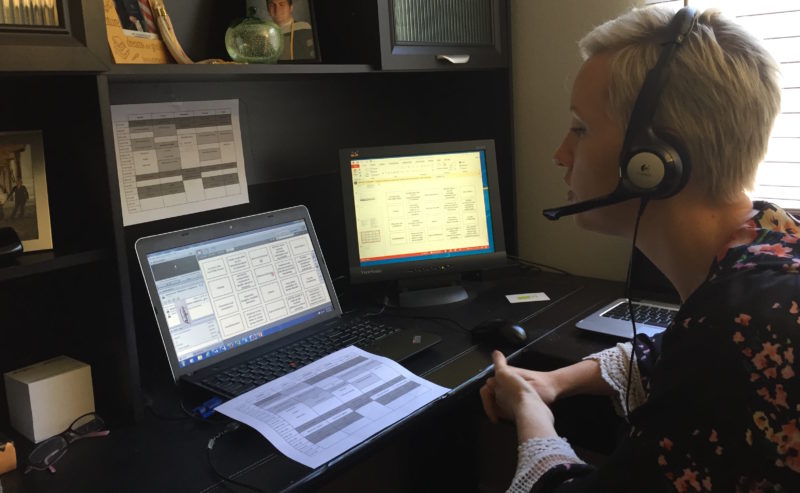

Kristin Bryant, a teacher at California Virtual Academies.

Kristin Bryant, a teacher at California Virtual Academies.

California Virtual Academy (CAVA) teachers want to do their job.

It’s that simple.

But virtual mountains of administrative tasks, a growing lack of supplies and support to their online classrooms, and their justifiable fear of speaking out on behalf of students makes it hard for CAVA teachers to do that job in a way that best supports students.

That’s why CAVA teachers voted in May 2014 for a union, which the state labor board certified in 2015 with the California Teachers Association (CTA). Since then however, the for-profit owner of CAVA, K12 Inc., has refused to sit at the bargaining table, or otherwise listen to the front-line teachers who know best how to educate their students. It is appealing the state board's decision to certify the teachers' union.

“We want CAVA and K12 to stop spending public money to challenge the lawful certification of CTA as our union, and to get to the table to address the problems at our school so we can make sure the students we serve receive the quality education they deserve,” said Sarah Vigrass, a 10-year CAVA teacher.

To that end, CAVA teachers last week launched a national, online petition drive aimed at K12 Inc., asking its managers to recognize the union, commit to investing in the classroom, and work with teachers to fix the school.

Follow the Money

CAVA is California’s largest online public charter school, serving nearly 15,000 students. Its appeal to many families is its flexibility—in Kristin Bryant’s AP Psychology class, for example, her students include young divers who spend their mornings jack-knifing into pools. Traditional school hours might not work for them, or the ones who are dual-enrolled in community college, but they can log into their virtual classroom each day. That same flexibility also is attractive to many CAVA teachers.

But unlike some other online charter schools, CAVA is managed by a for-profit company whose bottom-line interests can conflict with the needs of students. A March 2015 report from the research institute In The Public Interest (ITPI) notes this inherent clash: “One of CAVA’s functions is to act as revenue producer for its manager and primary vendor K12 California LLC (a publicly traded company). This can put the leaders of the company in a position where they must choose between maximizing profit to fulfill their responsibility to shareholders and fully investing in the education of public school children.”

Cost-cutting measures at CAVA include a growing lack of instructional materials, Vigrass noted. “When I first started working here, our students got huge science and art kits, and I was so thrilled by what they were provided. Now parents are expected to provide the instructional materials,” she noted. “They’ve also stopped giving parents teachers’ guides—and these are parents who are expected to be instructional guides! They are not given the tools that would help their child learn.”

Cost-cutting measures at CAVA include a growing lack of instructional materials, Vigrass noted. “When I first started working here, our students got huge science and art kits, and I was so thrilled by what they were provided. Now parents are expected to provide the instructional materials,” she noted. “They’ve also stopped giving parents teachers’ guides—and these are parents who are expected to be instructional guides! They are not given the tools that would help their child learn.”

CAVA also saves money by assigning administrative tasks to teachers, instead of hiring the education support professionals who typically do those jobs in regular public schools. In fact, the ITPI report notes that CAVA has a total of eight support employees for its 15,000 students. That means that when Bryant types good-bye to the students who have participated in her live psychology lecture on a recent morning, she has to spend the rest of her work day tracking down a virtual library of student attendance records, required parent/instructional coach reports, assessment results, and other bureaucratic checklist items. That time could be much better spent grading papers, responding to students’ texts or emails, or preparing for the next lecture.

“We do spend a lot of time chasing attendance or non-compliance. I would like to devote that much time to my students and making our classrooms look like they need to,” said Bryant.

These problems haven’t gone unnoticed by parents, lawmakers, and other community watchdogs. In September 2015, K12 Inc. was subpoenaed by an arm of the state attorney’s office, according to press reports, as part of an investigation into for-profit online charter schools.

More recently, a two-part investigative series published this month by the San José Mercury News questioned why K12 is raking in California taxpayers’ money—more than $300 million to date—while their schools show low student graduation rates, a lack of accountability, and working conditions that include telling teachers to inflate attendance and enrollment records.

Determined to Be Heard

“The way our school is being managed right, it’s not successful,” said Vigrass. But that doesn’t mean the online education model can’t work. It does mean that student success needs to be the priority.

Unfortunately, when teachers speak up to advocate for their students and classrooms, their words fall on deaf ears. “I’ve been here eight years, and that makes me not even like a grandma, but like a great-grandma in online learning!” said Bryant. “I would like for (managers) to talk to teachers about what we’re experts in, which is what our students need and how to deliver it to them.”

CAVA teachers, joined by NEA members, protest outside a K12 Inc. board meeting in Washington, D.C. last December.

CAVA teachers, joined by NEA members, protest outside a K12 Inc. board meeting in Washington, D.C. last December.

Many teachers also are afraid to shake the boat too much because they don’t have the protections of a collectively bargained contract, which would include typical due-process job protections. Instead, fed-up teachers just walk away for more stable (and better paid) positions. “We have such high turnover, it’s really hurting our kids,” Vigrass noted. “We have students who have had as many as five teachers, in the same class, in one year.”

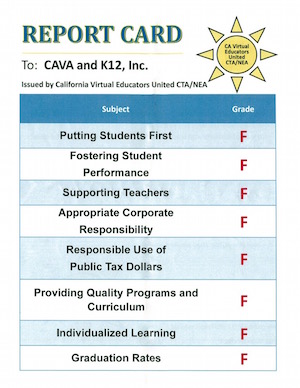

With frustrations growing, and the stakes for students so high, CAVA teachers are more determined than ever to be heard. In December, five traveled to K12 Inc.’s annual shareholder meeting in Washington, D.C., to deliver a report card of straight F’s. Their message was simple: CAVA and K12 are failing its students and teachers, and the time is now to invest in classrooms and put students above profits.

“CAVA and K12 are basically failing their staff and, more importantly, they are failing our students,” said CAVA teacher Mark Holtebeck to NEA's Education Votes. “The areas we graded them on came right from their mission statement—the things they said they wanted to do for students and teacher. They have not done any of that.”

In December, California state officials also urged CAVA to sit down at the bargaining table with its teachers. In a letter to CAVA management, State Superintendent Tom Torlakson wrote, “Teachers, students, and the families they serve have waited a long time to enter into this important collective bargaining process that they believe will lead to better communications and better conditions for learning.”

This week, educators across the nation are signing CAVA teachers’ petition, said CTA President Eric Heins, “because they know disrespect when they see it… It’s up to CAVA and K12 managers to do the right thing for these students and our communities and sit down to negotiate with CAVA educators at once.”