In the warren of Brockton Public Schools counseling offices, a police scanner flares. Somewhere in the city, a student’s mother, father, aunt or uncle, faces a brick wall, wrists handcuffed behind their back. They’re likely not coming home tonight.

In the warren of Brockton Public Schools counseling offices, a police scanner flares. Somewhere in the city, a student’s mother, father, aunt or uncle, faces a brick wall, wrists handcuffed behind their back. They’re likely not coming home tonight.

But the counselors in these offices, heads tilted to the noise of the street, as well as Brockton’s teachers, paraprofessionals, and other educators, are committed to making sure students who suffer traumatic experiences, like a parent’s jail time, do not have their own development arrested. For a decade, educators in Brockton, 30 miles south of Boston, have worked to create trauma-informed learning spaces. More recently, NEA and its affiliates, such as the Illinois Education Association (IEA), have carried the issue to the forefront of public education.

The numbers are stark: One in four U.S. students will witness or experience a traumatic event before the age of 4, and more than two-thirds by age 16.

These children do not—they cannot—simply close their eyes to what they’ve seen or experienced. With each forced eviction, each arrest of an adult in their home, each abuse to their own bodies, an instinctive trigger to “fight or flee” is pulled over and again.

Many educators know intuitively that no matter how hard they work, or all the different things that they try, there are still some children that they struggle to reach. Now, we know the science of why” - Audrey Soglin, Illinois Education Association

Over time, a child’s developing brain is changed by these repeated traumatic experiences. Areas that govern the retention of memory, the regulation of emotion, and the development of language skills are affected. The result is a brain that has structurally adapted for survival under the most stressful circumstances—but not for success in school.

“It was like an epiphany,” says Brockton teacher Michele Holmes, a veteran of 24 years, when she learned from the Massachusetts-based Trauma and Learning Policy Institute (TLPI) how the traumatic experiences of students affected their brains. “All of a sudden, everything made sense."

In fact, kindergartners who have suffered traumatic experiences score below average in reading and math, even when influential factors like household income and parental education are factored in, according to a 2015 study published in the journal Pediatrics. They also are three times more likely to have problems with paying attention, and two times more likely to show aggression to their classmates and teachers.

Eventually, they become the students who get suspended too often, feeding the school-to-prison pipeline.

Says Audrey Soglin, executive director of the Illinois Education Association, whose trauma-informed trainings have reached thousands of Illinois educators: “Many educators know intuitively that no matter how hard they work, or all the different things that they try, there are still some children that they struggle to reach. Now, we know the science of why.”

And now, with resources such as NEA’s “Teaching Children from Poverty and Trauma” handbook, NEA members also can know the “how” and “what” of trauma-informed education. And what works for students with trauma also works for non-traumatized students, too.

With a mixture of empathy, flexibility, and brain-based strategies, trauma-informed educators are creating cool, calm classrooms that work for all of their students—a kind of “universal design,” says Brockton’s head of counseling, John Snelgrove.

The Calming Corner

As a school-based counselor, Snelgrove worked years ago with a student who was quick to rage. “What’s going on?” Snelgrove asked. The answer: the student, his mom and his infant brother had lost their home and were sleeping in a laundromat during its closed hours—11 p.m. to 6 a.m.—then showering before school at a friend’s apartment.

Another parent told an administrator here, when asked why her child was sprinting home during school hours, that, “he’s been very needy since I was shot.”

These experiences directly shape your students’ brains. Consequently, the disruptive behavior that teachers often see—and punish—isn’t willful disobedience or defiance.

It’s a subconscious effort to self-protect. Their altered brains are screaming: Fight! Flee! Freeze! “It can look like these children are shutting down [or zoning out], but their brain is telling them, ‘you need to be safe,’” says Illinois special educator Kathi Ritchie, the facilitator of the NEA EdCommunities group on trauma-informed classrooms/strategies.

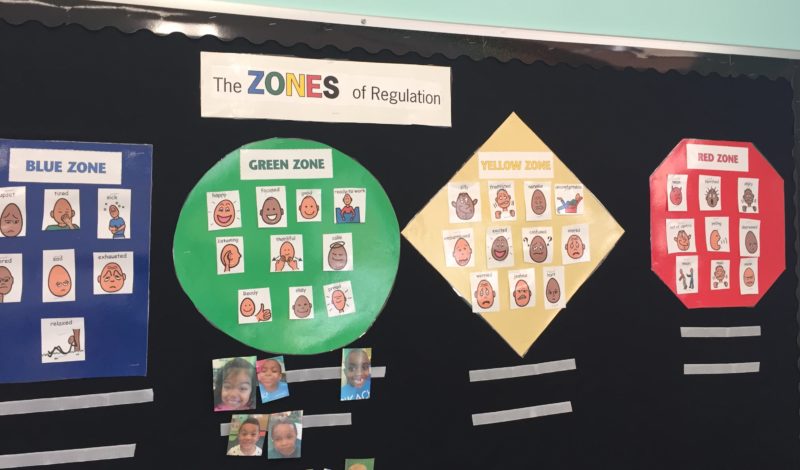

In Alexandra Kay's classroom, the "zones of regulation" help students identify their own feelings. Green includes happy and comfortable. There is no shame in saying you're feeling more yellow or red. It's a cue to take a break and calm down. (Photo: Mary Ellen Flannery)

In Alexandra Kay's classroom, the "zones of regulation" help students identify their own feelings. Green includes happy and comfortable. There is no shame in saying you're feeling more yellow or red. It's a cue to take a break and calm down. (Photo: Mary Ellen Flannery)

For example, “the behavior of wearing a hoodie pulled tight over their heads, curled up, head down on a desk…is similar to what they have had to do at home. They try to become invisible so that they are not seen by a drunken caregiver or abuser who comes home looking for a punching bag,” writes the author of the NEA handbook on teaching children from poverty and trauma.

So what is a trauma-sensitive educator to do? Instead of rushing to “punish, punish, and punish,” says Snelgrove, adults should respond in ways that make children feel safe. "Punishment alone, free from treatment and education, doesn't change behavior," says Snelgrove.

“Think before reacting,” says Holmes. “When the situation is charged, you have to step back and think ‘How can I bring this down and get back to learning?’”

In a corner of Alexandra Kay’s kindergarten classroom at the Barrett Russell School in Brockton, there’s a small tent where agitated students can curl up on a dimly lit pillow for a few minutes of quiet, and also a sand table, where they can run their fingers through the cool grains. “A sensory break,” Kay calls it. For her kindergartners who need a more active break from their desks, Kay also has a small trampoline.

Keeping in mind that the brains of some traumatized students are ill-adapted for language development or memory retention, Kay’s room contains lots of visual cues. The day’s events are scheduled in advance, routinized, and posted in successive, simply illustrated pictures: first breakfast, then seat work, followed by circle time. Behavioral expectations are illustrated, too: quiet mouths, quiet hands, quiet feet.

Ritchie also recommends teaching strategies that include asking students to repeat verbal instructions, and using more written instructions or visual prompts for multi-step directions, like a sticky Post-it note on a desk. Thoughtful breathing or mindfulness exercises can be helpful, according to the NEA handbook.

At Brockton’s George School, every classroom has a “thinking island,” where raging or “deregulated” students can retreat, and each island is equipped with a sensory basket that might contain a piece of fleece or satin ribbons, a scented votive candle (wick removed!) and a plastic bottle with colored water and glitter inside. Tip over the bottle, watch the glitter slowly descend, and calm down.

Not long ago, one of Holmes’ 7-year-olds asked her for the Play-Doh. “I said, ‘you know it’s not a toy…’ and she said, ‘I know! It’s a tool to caaaaalm dooooown.”

“If the kid needs the putty, let them play with the putty. If they need gum, give them gum! Be flexible!” urges Snelgrove. "We need to provide the materials, or create the conditions, that enable children to be successful."

“Flexibility” is a word or phrase you’ll hear often when talking with trauma-informed educators. “Mindset” is another one. “Our kids” is a third.

Three Things You Should Do Now

Learn more with these union-developed resources

- Download NEA’s “Teaching Children from Poverty and Trauma” handbook for information about the symptoms of trauma in students and classroom strategies to build community, teach social skills, and also enhance reading and other academic skills. (One sample tip: Greet every student authentically. Another: Write new vocabulary words in icing on cake!)

- Join the NEA edCommunities group on trauma-informed classrooms and strategies, so that you can join the discussion with your colleagues and also share in resources, like webinars and presentations.

- Visit Partnership For Resilience. The partnership, which has IEA at its head, has compiled a wealth of online resources, including explanatory videos and conference presentations.

The Ultimate Goal

The work of a trauma-informed educator isn’t about using a special “trauma curriculum,” it’s about giving students the support they need to access your regular curriculum, says Snelgrove.

“It can’t just be, ‘open your book, read the questions, and begin.’ I have 7-year-olds who think their parents will be deported,” says Holmes. They can’t learn until their fears are calmed and their attentions [are] re-focused. And they also can’t learn if they’re suspended or sitting in principals’ offices.

“The ultimate goal is to keep them in the classroom,” says counselor Kristin McKenna, of Brockton’s Arnone School, where the suspension rate fell by more than 40 percent after school-wide TLPI training.

This work also isn’t what people might imagine as typical “union work.” So why have NEA leaders and affiliates like IEA jumped headfirst into it?

In Illinois, it started with a conversation between IEA’s executive director and her pediatrician brother. It continued with IEA-sponsored film screenings of Paper Tigers, a school-based documentary from Walla Walla, Wash., that shows the impact of “one caring adult” in the lives of traumatized teens. Up to 300, 400, or even 500 IEA educators, parents, and community members were mesmerized at each showing, says IEA President Cinda Klickna.

“It was just so powerful—we had one [woman] who went to the screening and said, after 20 years of teaching, that it changed her entire thinking about what she does,” says Klickna.

Fueled by that kind of response, IEA’s work has rapidly expanded, in part through support from the NEA Foundation, to include three pilot programs in the districts south of Chicago. In those places, IEA’s partnership provides members with the professional development they need to be ready to teach, and the services students need to be ready to learn—like restorative dental care and treatment for asthma.

“I say, and I keep saying, advocacy for our members includes professional development. And when you find a topic that really resonates, and this resonates, it’s very exciting. It’s what they need to be able to do their jobs better.

“To us, it’s about leading the profession,” says Klickna.