AUSTIN, Texas—"Would you go?"

This is the question that silences 16-year-old Jacqui, tightens her wide smile into a thin line, and provokes a low sigh.

Her mother sits next to her—motionless—her gaze transfixed on a crack in the sidewalk.

The answer is no. Simply, reluctantly, painfully, no. If push comes to shove, and federal immigration agents deport Jacqui’s parents to Mexico, a country they left 18 years ago to find work, she would not go.

Jacqui would stay in the U.S., alone, to finish high school, go to college, and make good on her considered plans to earn a law degree. She is a citizen. They are not.

It’s a no-win situation that promises nothing but agony for millions of undocumented U.S. immigrant parents and their children.

“It is not something I like to think about,” says Jacqui quietly, closing the topic of conversation. Her mother still does not speak.

We are not criminals. We are mothers, and we are fathers. We are people who work, and who take care of our children. That’s it! Not criminals. Not criminals.” - Jacqui's mother

About one in 14 students, or 6.9 percent from kindergarten through twelfth grade, have at least one undocumented immigrant parent, according to a 2014 Pew Research Center report. Most are U.S.-born, American citizens, like Jacqui, while a much smaller number (1.4 percent) are undocumented themselves.

Their numbers vary widely across the U.S., from nearly 18 percent, or about one in five students, in Nevada, to 0.1 percent in West Virginia.

For the most part, their parents are like Jacqui’s. They crossed the border to find work at least a decade ago, statistics show, and then put down roots as their children grew. Jacqui’s mom has worked for years at a local dry cleaner, while her dad travels around Texas, installing specialized bathrooms.

Meanwhile, they go to church, shop at the H-E-B for groceries, stop occasionally for a lemonade at Starbucks, and volunteer often in their communities, including their schools and Parent Teacher Associations (PTA).

“We are not criminals,” Jacqui’s mother emphasizes. “We are mothers, and we are fathers. We are people who work, and who take care of our children. That’s it! Not criminals. Not criminals.”

Until recently, these undocumented parents felt safe mostly, or at least not so exposed, or hated, as they do now. But this spring and summer, as federal immigration raids increased, and as reports of immigration agents following school buses spread, a radiating fear unfurled in homes and schools.

With parents targeted, students are traumatized, unable to learn, educators say. “One of our kindergarten teachers had a little boy who brought a suitcase with him to class for two days,” says Colorado Education Association Vice President Amie Baca-Oehlert. “When she asked him what it was for, he said ‘I want to make sure I have my special things when they come to get me.’”

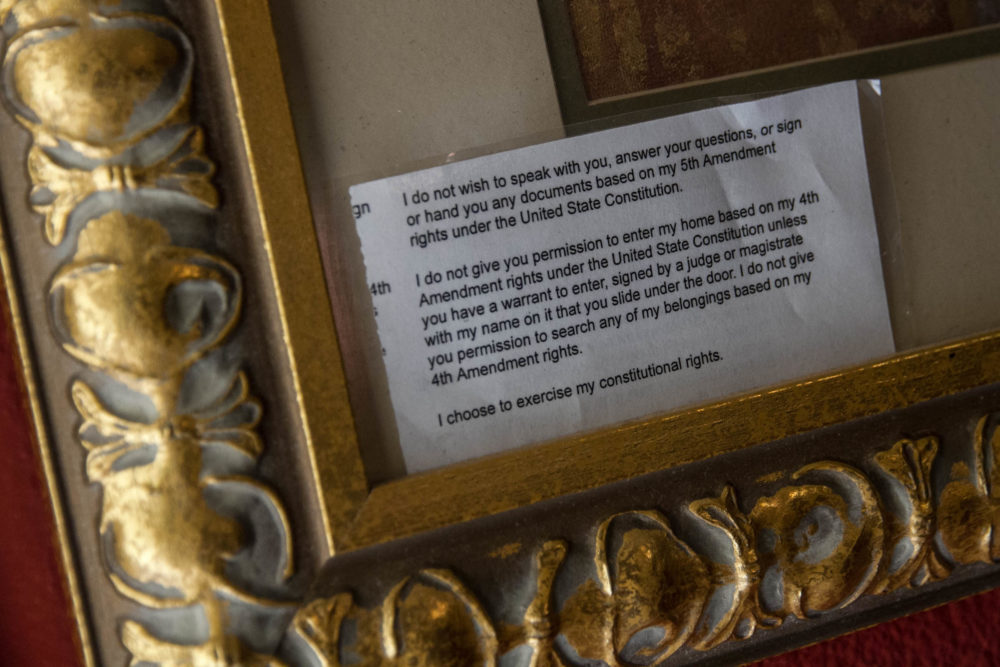

Printed on this small card, tucked into the corner of a picture frame in an Austin house, are sentences that 15-year-old Cristal, or 10-year-old Nicolas, must read aloud—through the locked door—if ICE agents come for their parents.

Printed on this small card, tucked into the corner of a picture frame in an Austin house, are sentences that 15-year-old Cristal, or 10-year-old Nicolas, must read aloud—through the locked door—if ICE agents come for their parents.

“These shocked and frightened families are our friends and our neighbors,” says NEA President Lily Eskelsen García of the shameful treatment. “As the Trump administration threatens our students, their families, and our way of life, we will not stay silent. As families turn to educators for solace and advice, we are going to accelerate our ongoing efforts.”

In Austin, an effort called “Know Your Rights,” led by Education Austin and funded, in part, by an NEA grant, provides much-needed, practical information to students, parents, and other community members on how to respond to immigration enforcement. Their work has been shared in Illinois, Arizona, and in Colorado, where the Colorado Education Association has partnered with advocacy groups to offer similar, statewide trainings. It also has been adapted by NEA for use across the nation.

Elsewhere, from Nebraska to New Mexico, Milwaukee to Maine, NEA members are using sample “Safe Zone” school board resolutions and district policies developed by NEA’s Office of General Counsel. The language is strong, legally defensible, student-focused, and relies on existing Supreme Court case law.

This is how educators care for their students, and this is how educators’ unions support that work, says Austin first-grade teacher Maria Dominguez.

“Our parents and students are scared. This is reality,” she says. “And if we’re a union that fights for our students, we need to do this work.”

Know Your Rights

Tucked into the corner of a picture frame, mounted inches from the front door of an Austin house, is a small card, about the size of a typical business card, from Education Austin’s “Know Your Rights” campaign.

Printed on the card are the sentences that 15-year-old Cristal, or 10-year-old Nicolas, must read aloud—through the locked door—if federal Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents come for their parents.

I do not wish to speak with you, answer your questions, or sign or hand you any documents based on my 5th Amendment rights... I do not give you permission to enter my home based on my 4th Amendment rights under the United States Constitution, unless you have a warrant to enter, signed by a judge or magistrate with my name on it that you slide under the door…

Nicolas and Cristal’s mother has been afraid to go to the nearby grocery store. Instead their dad drives, parks, and sends in the kids with a shopping list and money.

Nicolas and Cristal’s mother has been afraid to go to the nearby grocery store. Instead their dad drives, parks, and sends in the kids with a shopping list and money.

Nearby, on the dining room table, is a folder where Cristal’s mother, the president of her neighborhood school’s PTA, has collected all of the papers recommended by her children’s teachers. This includes copies of her children’s U.S. passports, as well as a power-of-attorney statement that would allow Cristal and Nicolas to stay in Austin, under the guardianship of their godmother, if their parents are deported.

A visitor does not ask what would happen to 5-year-old sister Stefanie, who somersaults across the sofa to nestle near her mother.

[Editor’s note: NEA Today is using first names only, in an effort to protect these students and their families.]

Be prepared is the message from their teachers. Get ready. Know your rights. Yes, you have rights, too! Led by Education Austin’s vice president, early-education teacher Montserrat Garibay, a former undocumented student who, in 2012, became a U.S. citizen after 20 years here, Austin educators have shared their message of empowerment with hundreds of parents and students. They also have provided trainings for their members and interested school and city officials.

“We advocate for our students to get glasses if they can’t see. We advocate for them to get special resources if they have dyslexia. This is just another way for us to advocate for them to get what they need,” says Dominguez, who herself was an undocumented student, brought here by her mother as a fourth grader.

Practical information is needed—and wanted. Education Austin’s trainings for educators and their meetings for families have been packed for months. On one Saturday in February, union leaders readied the library at Austin’s Becker Elementary for an expected 50 educators and school officials. But at 9 a.m., when the training was scheduled to begin, the line stretched out the door, the Austin Statesman reported. Garibay and others scrambled to move the event to the cafeteria to fit the 120-plus who showed up.

Five-year-old Stefanie is the least fearful—and aware—member of her family, but she senses the disruption in their routines.

Five-year-old Stefanie is the least fearful—and aware—member of her family, but she senses the disruption in their routines.

The training for educators, which has been adapted by NEA for use in any community, by any local NEA affiliate, provides at least 12 specific actions that educators can take to help their immigrant students. They include providing a safe space for students to wait if their parent or sibling has been detained, but also helping parents to prepare for possible deportation. Their model “rapid response” packet will include everything from updated school emergency contact forms to records of their children’s food allergies.

Cristal, a high school freshman, has been volunteering to help at Education Austin’s trainings, where she passes out contact information for attorneys, counselors, social workers, and others.

Her mother and father, who came to the U.S. nearly two decades ago for work, are terrified, she says. Her uncle hasn’t left his house in a month. “My parents want me to stay, in case, you know…They don’t want me to leave here. They say, ‘You go to college,’” Cristal says. Her dream school is Texas State University in San Marcos. Her dream job is to be a social worker. “I want to help families,” she says.

Two Things You Can Do (Now!) for Immigrant Students

1. Learn more about Safe Zone school board policies, get the answers to frequently asked questions, and download NEA’s sample school board resolution.

2. Check out NEA’s toolkit for “Know Your Rights” events.

But, she acknowledges, it’s hard to focus on school these days. “Teachers have to stop what they’re teaching to calm us down,” she says. But lately, many of her friends haven’t even been going to school. “Last month, I had just four kids in my class,” she says. Everybody else stayed home, hiding behind drawn curtains and locked doors.

This isn’t just an issue in Austin. During mid-February, one day after teams of ICE agents swept into a Las Cruces, N.M., trailer park and other homes, nearly 2,400 Las Cruces students stayed home from school.

“I went to the Wal-Mart last month and it was empty. Nobody is going there. Nobody is going anywhere. Our neighbor, she has depression, but she won’t even leave the house to pick up her medicine,” says Cristal.

“ICE could be anywhere.”

A Life Interrupted

Deportations during the Barack Obama years weren’t uncommon, but they focused on recent arrivals and criminals—those convicted of felonies or at least three misdemeanors. Law-abiding, here-for-decades parents of U.S. citizens weren’t targets.

Indeed, two years after creating the DACA program to protect students who had been brought to the U.S. as children, the Obama administration created DAPA, which offered work permits to their undocumented parents. The sense of relief that families would stay together was real.

“Nobody is going anywhere. Our neighbor ... won’t even leave the house to pick up her medicine,” says Cristal. “ICE could be anywhere.”

“Nobody is going anywhere. Our neighbor ... won’t even leave the house to pick up her medicine,” says Cristal. “ICE could be anywhere.”

But, in June 2016, with a 4-4 vote, the Supreme Court dismantled DAPA. And then, five months later, after promising to build a 50-foot-high wall along the 1,000-mile Mexican border, Donald Trump was elected president.

During the first weeks of his administration, arrests of immigrants rose 32.6 percent. But scarier to people like Cristal’s and Jacqui’s parents, the arrests of immigrants without criminal records more than doubled. Around Atlanta alone, ICE agents arrested 700 without criminal records—up from 137 the prior year.

Recent detainees include an El Paso, Texas, woman who was handcuffed at the county courthouse where she had gone to get a protective order from her abusive boyfriend—the very person who likely tipped off ICE agents to her presence, reported USA Today. Her only criminal offense was crossing the border illegally after deportation.

They also include Romulo Avelica-Gonzalez, a 48-year-old father of four girls, all born in the U.S., who had just dropped off his 12-year-old at school when he was pulled over on a Los Angeles street by two black, unmarked cars. In a video of his arrest, his 13-year-old daughter, who was in the car on her way to a different school, can be heard sobbing. Her father, who has lived in the U.S. for 25 years, has an 8-year-old misdemeanor drunk-driving conviction, the Los Angeles Times reported.

It is our job to make sure our most vulnerable students feel safe, supported, and in a place where they can learn" - Ed Ventura, library science teacher, Omaha, Neb.

Even more troubling, in April, the first confirmed deportation of a DACA recipient was reported by USA Today. Juan Manuel Montes, a 23-year-old community college student, was waiting for a friend to pick him up on the street when he was grabbed by ICE and just three hours later escorted across the Mexican border. More than 750,000 DACA recipients wondered if they were next. But, in June, Trump said he would leave DACA alone, reversing course on a campaign promise to dismantle it.

“I can feel how hollow my reassurances must sound when I tell [my students] everything should be fine,” writes Areli Zarate, a “DACAmented” Austin teacher who was brought here as an 8-year-old. “Truth is, I don’t know that. Nobody knows. Nobody can say whether some or all of my family will be torn from Austin.… No one can say definitively if I’ll be able to teach here come August, or if my students will be able to pursue their dreams.

“Try imagining yourself in my place, in this life interrupted, where the future is measured not in years, months, or even weeks but in days, sometimes hours.”

This fear is why Cristal’s mother stopped leaving the house to shop. Instead, Cristal’s father drives the 15-year-old to the grocery store, parks his pickup truck far from the entrance, and sends his daughter inside with the family’s shopping list.

Nicolas' mother, the president of her neighborhood school’s PTA, has collected all of the papers recommended by her children’s teachers that would allow Cristal and Nicolas to stay in Austin, under the guardianship of their godmother, if their parents are deported.

Nicolas' mother, the president of her neighborhood school’s PTA, has collected all of the papers recommended by her children’s teachers that would allow Cristal and Nicolas to stay in Austin, under the guardianship of their godmother, if their parents are deported.

How Can We Help?

Can we draw invisible lines around our schools to create safe zones for students? Can we construct spaces where they can focus on learning?

Educators are doing exactly that, across the nation. This spring, at the urging of hundreds of students and Milwaukee Teachers’ Education Association members, the Milwaukee School Board unanimously passed a “safe haven” resolution. Among other things, it bars district staff from assisting ICE in detaining people “whose only violation of law” is that they are—or are suspected of being—undocumented. It also prohibits sharing information about a student’s or guardian’s status without a valid court order or signed release.

Similar “safe zone” resolutions and policies have passed in at least 25 states. (See NEA’s map of safe zone districts.)

“It is our job to make sure our most vulnerable students feel safe, supported, and in a place where they can learn,” says Omaha, Neb., library science teacher Ed Ventura. “We all watch the news and see the hateful rhetoric and actions, and frankly, it’s scary. That is why I worked with our school board on this resolution.”

The Omaha Public Schools board resolution, which was based on NEA’s draft resolution, passed in February. But even if your school board is hostile, educators still can help their students feel safe, says Jacqui, the Austin tenth grader.

“Just knowing that they support me, that they know my situation, and they understand why I might act a little weird some days, or have difficulty concentrating…this is helpful,” says Jacqui.

This spring, Jacqui organized a walkout at her high school, in protest of Trump’s words and actions. She hopes to inspire others to also speak up.

“If you don’t talk, or make noise, they can’t hear you,” she says.

—NEA EdJustice writers Sabrina Holcomb, David Sheridan, and Kate Snyder contributed to this report.

Photos: Luis Gomez