We know the Baby Boomers, Generation X, and Y (aka, the Millennials), labels that have come to reflect the hopes and pessimism of their members. But it’s time for them to step back or at least share the generational spectrum with those who represent the first wave of a new generation of students aged 16 to 19—the young people who have been assigned the letter Z.

Born in the mid-1990s to the early 2000s, depending on whom you ask, more than a quarter of the U.S. population belongs to Generation Z. For now, most of its members are clueless that they have even been tagged. David Kinsella, a veteran teacher at Osbourn Park High School in Manassas, Va. recently learned about Generation Z. When he informed his students, they shot back questions and concern: “Did they run out of letters and decide to put us at the end of the alphabet?” Others, Kinsella says, worried whether Generation Z signified the fate of “the last generation and the end of the world?”

Kinsella teaches special education and general education students. Today, he laughs about the exchange. Back then, he assured the bewildered teens that they had nothing to fear. Their generation is different from the Millennials—think younger siblings—but Kinsella believes its members are filled with promise. He and other educators are among those taking note of who these teens are and poised to become in the classroom, the workplace, and in the world.

While science teacher Crystal Williams Gordon of Broadmoor High School in Baton Rouge, La. had never heard of Gen Zers, she knows them as her students. Gordon suspects that it won’t take long for her “tech savvy and adept” students to whip out one of their smart devices or cell phones to tune into what the scholars and pundits are saying most characterizes their generation.

Generation Z: The New Kids on the Block

They are “highly entrepreneurial, pluralistic, and determined to take charge of their own futures,” is how Northeastern University President Joseph E. Aoun describes Generation Z. This is what Northeastern found when it undertook a recent, national survey of young people aged 16 to 19. The survey, which produced one of the most compre- hensive profiles available of this generation, asked more than 1,000 students (half under age18, with 54 percent enrolled in high school) about their views on a range of weighty topics including their concerns about climate change, their ability to pay for college, will they ultimately be better off than their parents, the existence of God, the value of higher education, and whether their plans immediately after high school will include higher education, travel, military service, apprenticeship, or work.

Compared to millennials, said to be the most studied generation, awareness of the Generation Z label and research on its members is just beginning. Still, marketers, researchers, corporate recruiters, and universities like Northeastern are among those revving up in anticipation of serving, snagging, selling to, marketing, and yes, teaching this generation of teens and consumers: They’ve never known a non-digital world—one without smart devices and the Internet—and their perspectives on lifestyle and finances have been influenced by the weight of the Great Recession. The survey

found that when it comes to higher educa

tion and scaffolding a promising future, these young people are convinced that college is essential—Tommy Strei and Darius Wilson, both age 17, represent the majority (81 percent) of Generation Z when it comes to higher education.

Compared to millennials, said to be the most studied generation, awareness of the Generation Z label and research on its members is just beginning. Still, marketers, researchers, corporate recruiters, and universities like Northeastern are among those revving up in anticipation of serving, snagging, selling to, marketing, and yes, teaching this generation of teens and consumers: They’ve never known a non-digital world—one without smart devices and the Internet—and their perspectives on lifestyle and finances have been influenced by the weight of the Great Recession. The survey

found that when it comes to higher educa

tion and scaffolding a promising future, these young people are convinced that college is essential—Tommy Strei and Darius Wilson, both age 17, represent the majority (81 percent) of Generation Z when it comes to higher education.

Strei, a soft-spoken teen who “loves to learn,” says he’s been preparing for college and a career in nuclear engineering since he entered high school. A junior at Osbourn Park High School, Strei splits his time, gliding handily between a schedule packed with advanced and honors classes on his campus and college courses at nearby George Mason University through a statewide dual enrollment program. When he graduates in 2016, Strei will be the last of his three older siblings to attend college. By having them as role models, he says, the process of applying to his two top picks—Stanford University and MIT—will be easy. But what’s less clear, Strei says, is how to fully fund his college education without having to incur any kind of student loan debt. Strei is not alone: Two-thirds of Gen Z said they were “concerned” about being able to afford college.

“They are very pragmatic and know that the path to a good-paying job begins with a college degree.”

Look out Mom and Dad, almost a quarter of Gen Zers surveyed said they hope their parents will cover the bulk of college costs. A third of students are counting on grants and academic scholarships to supply the remainder. Over the years, Strei says his parents have offered to pay for his and his siblings’ college tuition at an in-state institution. But Strei says he may miss out on this financing if he chooses to study elsewhere. His ‘B’ plan? “I’m hoping to apply for and get an ROTC scholarship from the Navy to fund my college. It will also give me a steady career for five or six years after I graduate.”

The way forward for graduating senior Darius Wilson of Homestead, Fla., isn’t paved with a plan for funding his college-going dreams, but he’s not deterred. “Hopefully I’ll get financial aid to pay for a good part of it. And I know I will also have to work part time,” says Wilson who is being raised by his grandmother. Wilson, like 67 percent of Generation Z, is concerned about his ability to pay for higher education. Despite the price tag and the possibility of having to carry student loan debt, teen survey respondents (65 percent) said the benefits of earning a college degree outweigh the costs.

Wilson remembers “freaking out” with excitement the day he received his college acceptance letter from Florida Southwestern State College. Then, Wilson says, “Reality set in.” He was inching closer to his dream of becoming a social worker and to earning a college degree—something that no one else in his family has done. Low-income kids want the same things that their more affluent peers want when it comes to education, says Bridget Terry Long, the Saris Professor of Education and Economics at Harvard Graduate School of Education. “They are very pragmatic and know that the path to a good-paying job begins with a college degree.”

The Reality of the Rollercoaster

At 24, Marisa Manocchio is considered a Millennial, but she’s not much older than the Gen Zers she teaches engineering design at the Bio-Med Science Academy in Rootstown, Ohio. The first-year teacher and former NEA Student Program member says speaking the same language when it comes to social media and being able to use technology also gives her an instant connection with her students. But “being a mentor to them” is how Manocchio says she prefers to engage with the teens.

“The kids are great,” adds Manocchio, a first-generation college student who relied on scholarships and grants to pay most of her expenses. She made it, and today Manocchio sees no limits for Generation Z: “I want them to know that hard work and persistence pay off. I want to help them find their path.”

“The kids are great,” adds Manocchio, a first-generation college student who relied on scholarships and grants to pay most of her expenses. She made it, and today Manocchio sees no limits for Generation Z: “I want them to know that hard work and persistence pay off. I want to help them find their path.”

Bob Williams, an award-winning high school math teacher and Baby Boomer, is trying to do the same for his students in Wasilla, Alaska—many of whom were never told that college for them was possible.

“I have some really bright students, but many are unsure” and sometimes “uninspired” to climb higher," Williams says.

Gen Zers are emerging as the self-reliant ones, the survey concluded. Still, Williams says, high school, even for them, “can still be an emotional rollercoaster.” Meeting their emotional needs, he adds, is as important as the academic ones. That’s why Williams tries to offer even his top students a steady stream of positive, emotional reinforcements.

“Seventy percent of my success as a teacher,” says Williams, “is helping kids gain confidence that they can do it and be successful.”

Osbourn Park’s Kinsella fears that too often teens are trolling and looking to social media for the “validation they need and want.”

Shaking Things Up

Kinsella prides himself on keeping up with what’s trending in his students’ world—from what movies they’re watching on their tablets to what’s playing in their ears—but he maintains today’s teachers “have to understand who their teaching.” And it could mean adapting teaching styles to accommodate the learning needs of Generation Z.

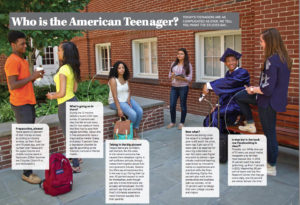

Who is the American Teenager? (Click to Enlarge)

Who is the American Teenager? (Click to Enlarge)

“I realize that I can no longer be the sage on the stage,” says Kinsella who, like many of his fellow teachers at Osbourn Park, is rethinking traditional lecture styles and his role as “all-knowing teachers.” It’s a new day: Gen Zers indulge in a significant amount of daily screen time (more than 52 percent) and are often looking to be entertained in the classroom. As a result, Kinsella says he’s trying something new—sometimes offering students the opportunity to walk to the front of the class and “teach” their peers. At Broadmoor High School, Gordon, a 2015 winner of the NEA Foundation’s Horace Mann Award for Teaching Excellence, says she is also shifting where technology is concerned.

“I don’t pretend to know everything about new technology,” Gordon adds, but she realizes she “needs to keep them engaged.” For help, she turns to “new, younger colleagues who are always searching for the next new thing in terms of technology. And they are always willing to share.”

Teaching Generation Z, Kinsella says, has offered him and other teachers an unexpected sigh of relief.

“Today’s students don’t need to think that their teacher is perfect,” he says. “They just want to know that we are willing to work with them.”