In May, the Texas State Board of Education (SBOE) invited feedback on a new textbook it had commissioned for a Mexican-American Studies elective offered to the state's schools. Augustin Loredo, a social studies teacher in Pasadena, TX, downloaded the pdf from the state education web site and paged through the 500 + page document.

In May, the Texas State Board of Education (SBOE) invited feedback on a new textbook it had commissioned for a Mexican-American Studies elective offered to the state's schools. Augustin Loredo, a social studies teacher in Pasadena, TX, downloaded the pdf from the state education web site and paged through the 500 + page document.

If formally approved, "Mexican American Heritage" by Valerie Angle and Jaime Riddle, it is safe to say, won't be a fixture in Loredo's classroom.

“I’m not touching it. That book will never be used with my students,” he states categorically. Loredo then catches himself and backtracks – just a little.

“No, wait. Maybe I’ll introduce it to my students as how not to teach Mexican American studies.”

Loredo, who has been teaching the subject for 11 years at South Houston High School, says the book is a travesty. He's not alone. Educators and activists across the state have mobilized this summer to call attention to the racial stereotypes and historical inaccuracies that are littered throughout the book and demand that the SBOE reject it and start over.

For example, in a section on foreign business investment in Mexico in the late 1800s, the authors wallow in gratuitous stereotyping:

"[Industrialists] were used to their workers putting in a full day’s work, quietly and obediently, and respecting rules, authority, and property. In contrast, Mexican laborers were not reared to put in a full day’s work so vigorously. ...There was a cultural attitude of ‘mañana,’ or ‘tomorrow,’ when it came to high-gear production. It was also traditional to skip work on Mondays, and drinking on the job could be a problem."

Then there's this passage on assimilation:

“Cubans seemed to fit into Miami well, for example, and find their niche in the business community. Mexicans, on the other hand, seemed more ambivalent about assimilating into the American system and accepting American values…The concern that many Mexican-Americans feel disconnected from American cultures and values is still present.”

The book also claims the 1960s-era Chicano Movement "adopted a revolutionary narrative that opposed Western civilization and wanted to destroy this society."

Video: "Offensive Stereotypes, Distorts History"

The text really isn't about Mexican American heritage, says Ovidia Molina, vice-president of the Texas State Teachers Association.

"It's more concerned with how White people have to deal with people coming from Mexico. It portrays Mexicans as not wanting to assimilate - just looking to take over and grab whatever they can get."

What Happens in Texas Doesn't Stay in Texas

What is exasperating is that the proposed book materialized out of a modest but genuine victory for educators and students in Texas. In 2015, the SBOE voted to include Mexican American studies as an elective in the state curriculum. That wasn't quite what educators like Agustin Loredo wanted. They had petitioned for the course to be more formally embedded in the state curriculum. Still, the result was chalked up as a win - especially in the wake of Arizona's efforts to ban outright the teaching of ethic studies. The board then asked publishers to submit textbooks on Mexican American studies.

"Once you allow students to believe that their families have not contributed to the fabric of this country, or let them believe that their ancestors are out to destroy it, you are devaluing them as citizens and as human beings" - Agustin Loredo, teacher, South Houston High School

So far, so good. Unfortunately, the only submission received was from a company led by Cynthia Dunbar, a right-wing ideologue and former board member who once called public education "a subtly deceptive tool for perversion." Dunbar hired writers who had no concrete expertise in the field of Mexican-American studies.

The result? A textbook that "has the look of a task given to an intern who has been told to cobble together what they can using the Internet,” said Dr. José María Herrera of the University of Texas at El Paso.

How a victory for ethnic studies in Texas generated such a textbook "does seem a bit like a ‘be careful what you wish for,' moment," says Molina.

Given the perennial circus-like atmosphere surrounding Texas' highly-politicized textbook adoption process, fending off outage fatigue might be difficult. Since 2010, the SBOE, with its conservative majority, has repeatedly flexed it muscles in altering how U.S. history and science is taught in schools, while proudly championing its vetting process that relies on regular citizens with little or no academic background. Textbook publishers, eager to appease this enormous market (the second largest in the nation), tailor materials accordingly - which then find their way onto desks in classrooms not only in Texas, but across the country.

But educators are determined to fight the adoption of the Mexican-American heritage textbook. To do anything less, says Loredo, would be a disservice to students in a state where Latinos now make up more than 50% of the public school student population. The seemingly endless battle with a right-wing school board over textbooks may be tiring, but the risk of inaction for students is too great.

"Once you allow students to believe that their families have not contributed to the fabric of this country, or let them believe that their ancestors are out to destroy it," Loredo says, "you are devaluing them as citizens and as human beings."

A White Redemption Narrative

Nicholas Ferroni, a history teacher at Union High School in New Jersey, doesn't use the textbook issued by the district. "If I did, I would be teaching White History to my Black students and male history to my female students," he says.

"We indirectly teach kids to be racist and sexist by downplaying the roles of specific groups," says Ferroni. "Too many textbooks enable this thinking. They can make that sizable of an impact."

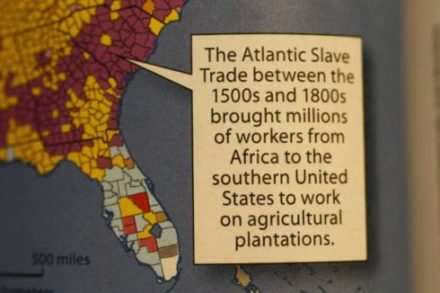

This caption identifying slaves as "workers" appears in a McGraw-Hill World Geography textbook. One parent's protest - fueled by a video that went viral - forced the publisher to apologize and promise a correction.

This caption identifying slaves as "workers" appears in a McGraw-Hill World Geography textbook. One parent's protest - fueled by a video that went viral - forced the publisher to apologize and promise a correction.

Naomi Reed agrees. A social anthropologist and post-doctoral fellow at the University of Texas at Austin, Reed has studied the nexus of race and education, specifically textbooks, for more than a decade. She doesn't hesitate to draw a straight line between the negative stereotypes and distortions found in some texts and the racist beliefs that lead to racial violence. It's a point she made in a recent article provocatively titled, "Are Texas Textbooks Making Cops More Trigger Happy?"

Reed focuses her analysis on one popular AP U.S. history textbook, The American Pageant by David Kennedy, which she says is replete with the kind of revisionist history that creates a "white redemption narrative." Potentially powerful discussions of slavery, Jim Crow, and the Civil Rights Movement, Reed says, are diluted by passages focusing on the negative impact on white people.

"Something bad happens to a Black person and the story is retold or recast as something bad happening to a White person," she explains. "You see it in textbooks and you see it in the media today in the coverage of police shootings. Somehow the narrative becomes less about black oppression and more about white victimization. It's everywhere."

"Something bad happens to a Black person and the story is retold or recast as something bad happening to a White person... the narrative becomes less about black oppression and more about white victimization"- Naomi Reed, University of Texas at Austin

"Something bad happens to a Black person and the story is retold or recast as something bad happening to a White person... the narrative becomes less about black oppression and more about white victimization"- Naomi Reed, University of Texas at Austin

In 2015, a Houston-area parent was appalled to find a caption in her son's McGraw Hill World Geography textbook that called slaves "workers." She took to social media and soon the publisher was furiously backtracking, insisting it was only an "editing error," and promising to deliver a corrected copy. But even after this incident and the countless embarrassments that came before it, the Texas SBOE voted again in late 2015 to stand by the citizen panel charged with reviewing textbooks.

Reed says that until the board implements a proper academic review of classroom materials and other necessary reforms, too many students in Texas - and potentially across the country - will be exposed to a distorted and exclusionary version of history.

A more rigorous vetting process may have served as a roadblock to Cynthia Dunbar's "Mexican American Heritage." The SBOE is set to hold public hearings on the textbook in September and then vote on whether to adopt it for Texas public schools in November. Agustin Loredo is hopeful that the board will recognize that Dunbar's book shouldn't be allowed anywhere near any classroom. He is quick to add, however, that the larger battle - particularly in the current toxic national political climate - still looms.

"Why would they oppose classes that are proven to increase graduation rates and empower students to succeed? Because they teach all kids - White, Black and Latino- different perspectives. That's a threat to a lot of people and it's what we're up against."