On January 18, 2018, the Electronic Classroom of Tomorrow (ECOT), Ohio's largest K-12 virtual school, abruptly closed its doors for good. The move, which left its 12,000 students scrambling for another option halfway through the academic year, came amidst escalating scandals over the for-profit cyber charter's operations. ECOT had been inflating its attendance records to siphon off more state funds. At the time of ECOT's demise, the Ohio Department of Education was trying to recoup $80 million in improper payments based on years of deceptive enrollment reports. Its academic record was also abysmal. More than one-third of Ohio's dropouts were ECOT students, and the school consistently ranked near the bottom on state assessments.

On January 18, 2018, the Electronic Classroom of Tomorrow (ECOT), Ohio's largest K-12 virtual school, abruptly closed its doors for good. The move, which left its 12,000 students scrambling for another option halfway through the academic year, came amidst escalating scandals over the for-profit cyber charter's operations. ECOT had been inflating its attendance records to siphon off more state funds. At the time of ECOT's demise, the Ohio Department of Education was trying to recoup $80 million in improper payments based on years of deceptive enrollment reports. Its academic record was also abysmal. More than one-third of Ohio's dropouts were ECOT students, and the school consistently ranked near the bottom on state assessments.

ECOT's spectacular failure became a central issue in the 2018 campaign for Ohio attorney general and governor. The voters rightfully want to know: How could hundreds of millions of state dollars be squandered on a school fraught with fraud, mismanagement, and a shoddy academic record?

Welcome to the world of for-profit, virtual charter schools.

ECOT was the indisputable poster child for Ohio's struggling, unaccountable charter sector, says Becky Higgins, president of the Ohio Education Association (OEA). Over the years, OEA relentlessly pushed state lawmakers to scrutinize ECOT's operations and adopt stronger accountability measures to protect students and taxpayer funds.

It would be a mistake, however, to look at ECOT as one "bad actor." Six months after ECOT closed, the Virtual Community School of Ohio also collapsed after being told to repay $4 million in state funds.

"Not only are the students being badly served, but the taxpayers are being fleeced. And at a time of declining state revenues, it's all the more important that tax dollars are well spent," said Higgins.

In 2017, the National Education Association's Charter School Taskforce recommended that because of the "combination of inherent limitations they pose to the healthy social and emotional development of students, along with their particularly dismal student outcomes, full-time virtual charter schools should not be authorized."

In January 2018, ECOT, the largest virtual K-12 school in Ohio, closed its doors after failing to repay $80 million in state funds.

In January 2018, ECOT, the largest virtual K-12 school in Ohio, closed its doors after failing to repay $80 million in state funds.

While just under half of all virtual schools in the nation are charter schools, together they accounted for roughly 75 percent of virtual school enrollment in the 2017-18 school year.

Would-be ECOTs exist in many of the 27 states that have opened their doors to virtual charters, says Michael Barbour, Associate Professor of Instructional Design at Touro University in California.

"Especially in states that were early entrants into the virtual charter world, there was very little oversight or accountability built into them," Barbour explains. "Programs were set up by individuals with a strong background in business. For-profit authorizers play a very direct role in the operations of the school. You have voluntary boards handpicked by the corporations whose sole responsibility is to sign a contract with that corporation to operate that school."

Behind every opening of a full-time, for-profit, virtual charter school, says Barbour, is "an abdication of the public responsibility for education."

Profits Over Students

The policies and practices of these schools should be subject to increased federal oversight, according to two U.S. senators. Sherrod Brown of Ohio and Patty Murray of Washington recently called on the General Accounting office (GAO) to scrutinize how the lack of accountability and transparency is affecting student outcomes.

“Most states distribute funding to virtual charter schools as they would to brick-and-mortar schools," Brown and Murray wrote in their letter to the GAO. "And yet, there is limited information on how operators allocate those public dollars to educate students and manage company operations. This is especially problematic as the majority of virtual charter schools are either explicitly operated by or connected to for-profit companies that have perverse incentives to minimize the cost of instruction and student supports in order to boost their bottom line."

The letter coincided with a scathing new report by the Center for American Progress on the academic performance and financial practices of for-profit virtual charter schools.

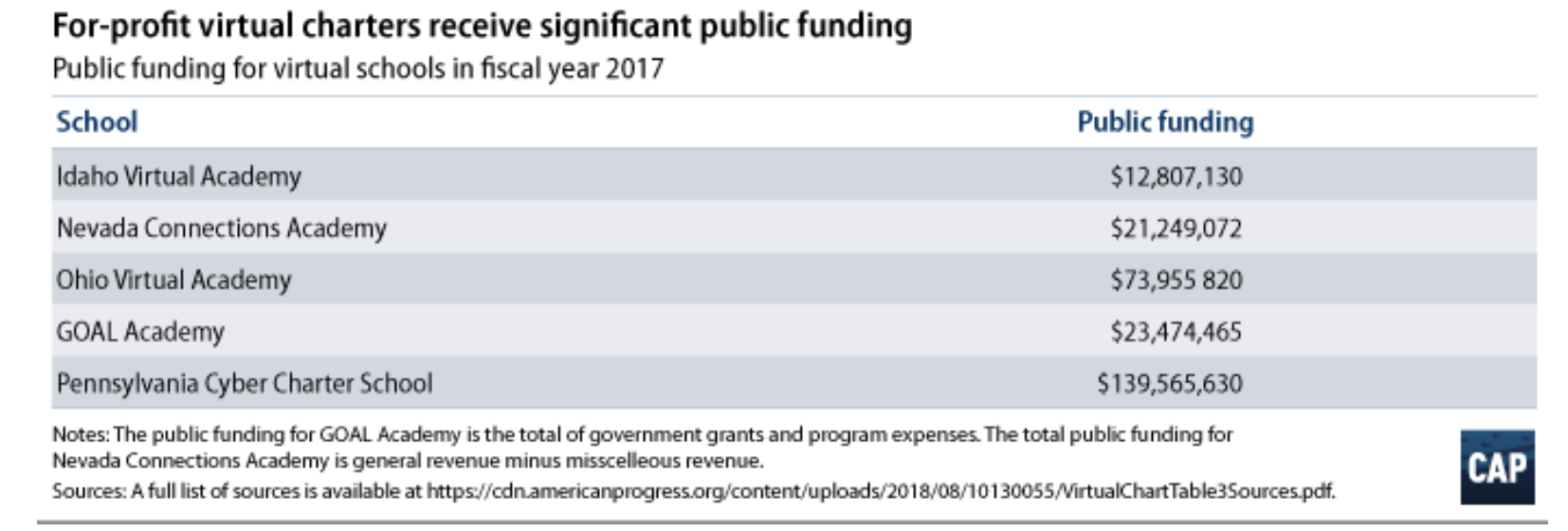

Meg Benner and Neil Campbell analyzed outcomes at the largest, for-profit virtual charter schools in five states. Many of these schools are run by K12 Inc., the largest such operator in the nation, serving an estimated 30 percent of students enrolled in these schools.

Source: "Profit Before Kids," Center for American Progress, 2018

Source: "Profit Before Kids," Center for American Progress, 2018

"[Accountability] policies have not kept pace with the growth of virtual education, enabling many for-profit operators to take advantage of fully virtual instruction to boost their bottom line and drive dollars away from instruction at the expense of student outcomes,” said Benner, senior consultant for K-12 Education Policy at CAP.

The extent of the failure detailed in the report is staggering:

- For-profit virtual charter schools graduate about half of their students, which groups them among the lowest-performing schools in their state. Furthermore, for-profit cyber charters have much lower graduation rates than nearby urban school districts that generally serve more low-income students.

- The schools generally perform below the state average for third-grade English language arts and eighth-grade math proficiency.

- Most of the large virtual charter schools in CAP’s analysis also fell far below states’ expectations for students’ academic growth.

Benner and Campbell also take a hard look at the financial records of K12 Inc., which reveal a prioritizing of growth at the expense of results: "Despite concerning outcomes across many of K12 Inc.’s virtual charter schools, the company’s 2018 annual report demonstrates that it continues to divert resources to grow enrollment, thereby limiting funds to improve academic programs."

Then there are the hefty compensation packages doled out to K12 Inc. executives. Benner and Campbell say the compensation of K12 Inc.’s top five executives is "comparable to the national average cost of educating almost 1,300 public school students."

Political Pressure

In addition to recommending rigorous new accountability mechanisms for all virtual charter schools, the authors endorse banning for-profit companies from opening and operating these schools. Lawmakers would have to be careful, however, to tailor the language very specifically to cover any arrangements a for-profit entity may use to to avoid compliance.

"The majority of virtual charter schools are either explicitly operated by or connected to for-profit companies that have perverse incentives to minimize the cost of instruction and student supports in order to boost their bottom line." - U.S. Senators Sherrod Brown (OH) and Patty Murray (WA) in a letter to the General Accounting Office

"These guys don't have much experience in education," says Michael Barbour. "But they do know business and they know how to find loopholes to get around regulations."

In September, California Gov. Jerry Brown signed into law a bill, supported by the California Teachers Association, prohibiting for-profit companies from owning and managing charter schools, a major step for a state that has 10 percent of its 6.2 million K-12 students in charter schools. Strong political opposition, however, appears to have stemmed the expansion.

In Indiana, educators have been lobbying the legislature to curb the growth of the states' poorly performing virtual charter schools, where more than 12,000 students are enrolled. Their record, says the Indiana State Teachers Association (ISTA), is "wholly unimpressive for kids and taxpayers." ISTA advocates a moritarium on new virtual schools and a change in the funding formula so that performance, not enrollment, determines how much they receive from the state.

As the fallout of the ECOT debacle continues, Ohio lawmakers have passed a series of measures in 2018 designed to strengthen accountability and require fraudulent charter school funds to be returned to school districts. Educators and many lawmakers say more needs to be done, because another ECOT could very easily happen. After all, 4,000 of ECOT students this spring transferred to another virtual charter school, Ohio Virtual Academy - owned and operated by K12. Inc.