When Harvard Professor Robert Putnam began working on his new book, "Our Kids: The American Dream in Crisis," five years ago, his goal was to make income inequality and the opportunity gap the dominant domestic issues of the 2016 presidential election. The book appears to have done its part. It's probably no coincidence that soon after Putnam briefed Jeb Bush on the issue, the GOP presidential candidate-in-waiting declared that closing the gap should be a national priority. Putnam is also a longtime acquaintance of President Obama, who has recently stepped up his call for both political parties to address the crisis of poverty.

When Harvard Professor Robert Putnam began working on his new book, "Our Kids: The American Dream in Crisis," five years ago, his goal was to make income inequality and the opportunity gap the dominant domestic issues of the 2016 presidential election. The book appears to have done its part. It's probably no coincidence that soon after Putnam briefed Jeb Bush on the issue, the GOP presidential candidate-in-waiting declared that closing the gap should be a national priority. Putnam is also a longtime acquaintance of President Obama, who has recently stepped up his call for both political parties to address the crisis of poverty.

In "Our Kids," Putnam (whose best-selling 2000 book "Bowling Alone:The Collapse and Revival of American Community" also stirred conversations) uses personal narratives and a wealth of compelling data to weave together a grim and sobering picture of what it is like to grow up poor and isolated in the United States. While the book may not offer up the kind of sweeping proposals that many believe are necessary to tackle inequality, Putnam's primary objective is to bring the crisis into focus for the average citizen, who is not keenly aware of the plight faced by millions of American children.

While the picture may be bleak, Putnam believes, as he recently told NEA Today, that the U.S. could be on the cusp of a new era of shared responsibility and "return to being a nation where there are only 'our kids,' not just 'my kids.'"

The discussion about inequality, especially in the media, has usually been focused on the "1 percent" or the anti-Wall Street protests. Was the motivation behind "Our Kids" to refocus the dialogue to make the issue more compelling to the wider general public?

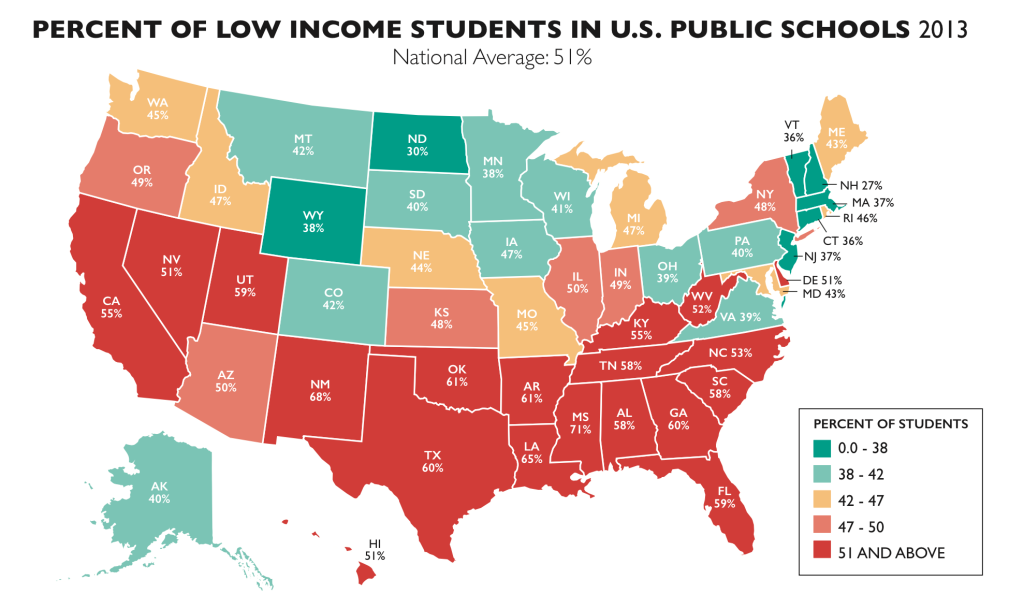

Robert Putnam: Yes, I thought the underlying problem – growing economic inequality – was not getting adequate attention, but especially how it affected our children. There are two big things that have happened that deeply affect kids. One is growing economic inequality. The second – well-understood by scholars but not at all by average Americans - is the growing social segregation along class lines. This is rich and poor people increasingly living in different neighborhoods, increasingly going to different schools, increasingly marrying within their own socioeconomic group. So we are living as two separate Americas.

The implications for children, however, have not been fully understood and I want people to understand how bad it's gotten for them. So if you frame the issue around its impact on kids, that would make it easier for people to appreciate what it means and, more importantly, make them act on it.

Many Americans have a fairly strong resistance to any economic idea or proposal that smacks of being "European." Isn't it hard then to have a real national discussion when even the suggestion of a small tax increase on more affluent people gets tarred as "socialism."

RP: I would say that we are living in probably the most individualistic, the least solidaristic time in our history. Many people think that this is simply how our country is, but that’s just not accurate. We go through big waves of emphasis on individuality and then a wave of emphasis on community. At the turn of the 20th Century, right after the Gilded Age, the public philosophy at the time was Social Darwinism - the idea that everybody would be better off if they just looked after themselves. This is deeply similar to the Ayn Rand libertarianism that seems dominant today.

So we began the last century with extreme individualism, but during the next few decades through the 1960s, we focused more on our shared interests and our obligations to one another. We became much more egalitarian. So we've turned this around before and we can do it again if we really begin to focus on the plight of these kids.

Source: Southern Education Foundation

Source: Southern Education Foundation

The book has a long chapter on schooling, but it’s hard to talk about public education and the opportunity gap without getting into the education reform movement and the policies of the past decade or so. What in our view has been constructive and harmful about this debate?

RP: Well, I should first say that when I wrote this book, it certainly wasn't my intention to get into the “education wars” but now I find myself in the middle of them!

But Americans have a very bad habit: they blame our schools for everything. The source of our problems are not in our schools. Schools today marginally narrow the opportunity gap. Could they close the gap some more? Of course, and that is the debate we should be having - a fact-based discussion, not based on ideology, that would help narrow the opportunity gap, recognizing first that the sources for the problem lie outside the schools. I don’t know why that idea should be so controversial to many reformers.

It has a lot to do with money, right? How we fund our schools is inherently unequal but changing those formulas is enormously complex and politically very difficult. So where does today's political reality allow us to go in terms of investing more in kids?

RP: Again, we've been there before. The decision in the early 20th century to invent the high school - the idea of a free and universal public education - accounts for virtually of the nation's economic growth in the 20th century. Because we dramatically increased the education of our workforce. We leveled the playing field. But it was not uncontroversial because it required rich folks in town to agree to pay higher taxes so that poor kids in town could also get a free public education. The change in mood at the turn of the 20th century encouraged everybody in these communities to think it was part of their obligation and would serve their own interest in the long run if all kids got a free secondary education. But as you say, how we fund our schools today is a very, very complex issue.

I think we have to Invest in free and widely available early childhood education and widely available community college or post –secondary eduction. There's real political support for these initiatives.

In the book, you discuss the lack of funding for extracurriculars in low-income schools and how parents have to shell out their own money to pay for them. How is the lack of extracurriculars so damaging and hasn't the high-stakes era contributed to them being devalued?

We know from the evidence that extracurriculur activities foster what are often called "soft skills," things like teamwork, grit, communication, and so on. These are skills that are hugely important for success in life. That's causation - if you participate in, for example, sports and you learn those skills, you will in fact be more attractive to employers.

President Barack Obama and Harvard Professor Robert Putnam, author of "Our Kids," discuss overcoming poverty at Georgetown University on May 12, 2015.

President Barack Obama and Harvard Professor Robert Putnam, author of "Our Kids," discuss overcoming poverty at Georgetown University on May 12, 2015.

And that's why we have extracurricular activities. They were introduced in the period I spoke about earlier precisely because the educational reformers at that point thought that school should be responsible for inculcating soft skills as well as hard skills. They attached music, art and sports to schools for these reasons. It worked and it was great for most of the 20th century. But then we got mired in this misguided idea that sports and music and so on are just frills and something that your parents should pay for. We did the dumbest possible thing and reversed this reform that had worked so well.

And of course when you take way these opportunities,students become disengaged from school and drop out. As for standardized testing, accountability is important, but in a high-stakes context, only what gets tested is what gets taught.

Another trend you address that I think most people aren't aware of when talking about inequality is the "savvy" gap. How does it exacerbate the opportunity gap between low-income and more affluent students?

Low-income students generally find it much more difficult—often impossible—to navigate any institution: what courses to take, how to get an internship, even what a “community college” really is. Most of us take for granted a level of institutional savvy that is beyond the reach of most poor kids - not because of lack of intelligence, but because of lack of mentors and other caring adults. This is an issue that must be addressed to close the opportunity gap.

Where do you see the seeds of real progress being planted? What's going on that can give us optimism?

I see promising experiments in early childhood education, home visiting, and even minimum wage requirements (among other things) springing up in states and communities across the country. Not all these experiments will prove successful, but they evince a growing grassroots desire to begin to address the opportunity gap. That’s the way that social reforms in the United States typically begin, even when in the end national initiatives are ultimately required, as well.

When I speak to audiences, I always find myself saying, ‘I am not trying to make America like Sweden. I’m trying to make America like America.’ The idea that you can reverse a high level of inequality and begin to close opportunity gaps through investing in other kids is an American value. That gives me hope.

Our kids are like the canary in the mine. They show us how self-centered we’ve become as a people and how much we can gain if we begin investing in their lives.