Conversations around student poverty took center stage last week in Washington, D.C. when leading experts gathered at a symposium, hosted by the National Education Association, to examine poverty’s effects on child development, promising practices, and policy recommendations beyond the schoolhouse.

Conversations around student poverty took center stage last week in Washington, D.C. when leading experts gathered at a symposium, hosted by the National Education Association, to examine poverty’s effects on child development, promising practices, and policy recommendations beyond the schoolhouse.

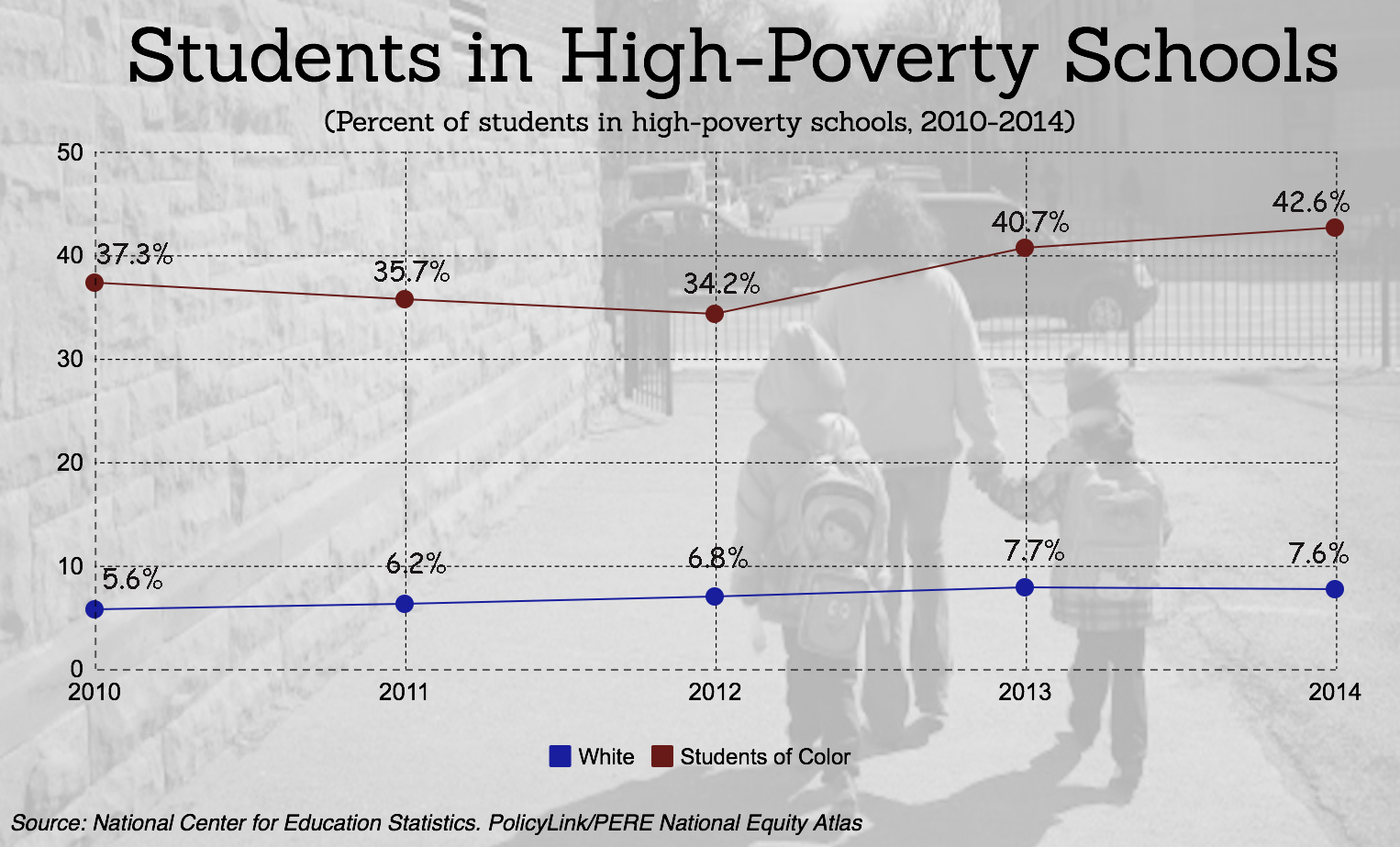

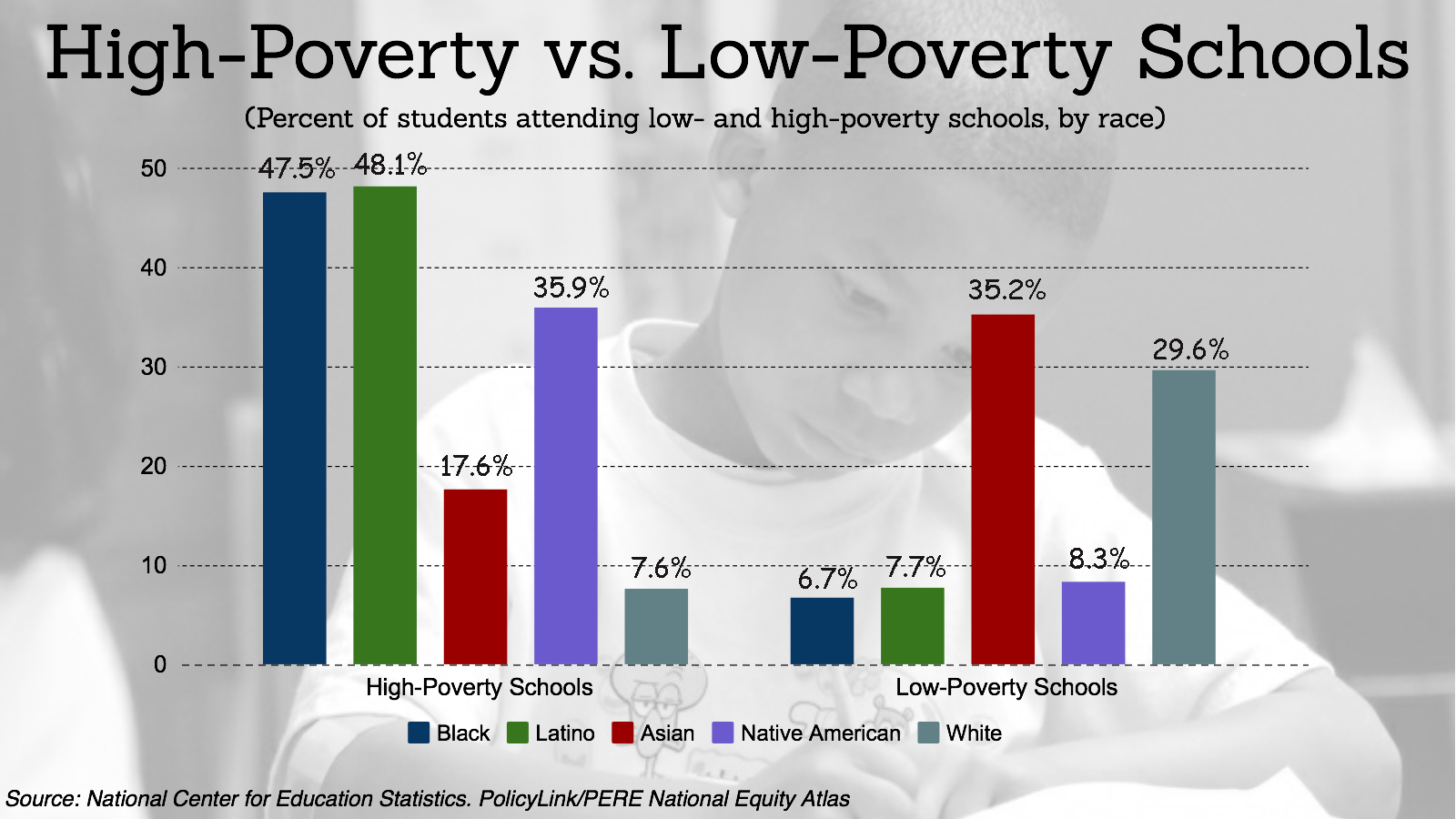

The statistics on child poverty are alarming: 15.5 million U.S. children live in poverty, one in five children receive food stamp assistance, and more than 50 percent of public school students qualify for free or reduced-price lunches.

“Poverty is a tragedy,” said NEA President Lily Eskelsen García during her keynote, “…and their only hope is what they find in that public school,” referring to schools that integrate academics with community services, such as health and social services, youth and community development, and community engagement.

"Why aren’t we making every public school like our best public school?" Why aren’t we improving the community as we improve our public schools? Make the case that every public school should look like the best public school,” Eskelsen García said.

Policies Working Together

Three different panels led the day’s conversation, which ranged from poverty’s effect on brain development and how some early returns have found structural differences in the brains of children to dispelling the myths and negative perceptions of poor people. The narrative of “black and brown kids don’t care about their education” must change, said Zakiyah Ansari, advocacy director of the New York State Alliance for Quality Education. “It’s a narrative we’re pushing back on.”

While educators were on hand to discuss the disconnect between policy and practice, policymakers underscored that public education is just one path to the road of opportunity, and on its own, can’t lift all poor students from where they begin.

Panelist Debby Chandler works in Student Services for Rogers High School and said it best: “Just because you’re born into poverty doesn’t mean you have to stay there. It’s everyone’s job to help.”

This means looking at policies that offer affordable housing, food assistance, economic security. Renée Wilson-Simmons, director of the National Center for Children in Poverty, noted that often policies conflict with one another. “We give with one hand and take with the other,” explaining that the fight to increase the minimum wage to $15 should not be met with resistance if reducing poverty is a priority. The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) should not be stripped or abandoned.

A better approach to addressing poverty is to talk about how policies work together “so it’s not the flavor of the month,” said Martin Blank, president of the Institute for Educational Leadership and director of the Coalition for Community Schools.

What would this look like in practice? MaryLee Allen, director of Policy at the Children’s Defense Fund offered some insight.

“There are may programs out there that are working—EITC, the SNAP program, and housing vouchers—and if we were to combine 9 policies that we know work and increase those policies on ending child poverty, what would be the impact?

In her work, she’s seen how combining and investing more money into policies that help people work and make a living wage with those that ensure the basic needs of children are met reduced the poverty levels of African American children by 60 percent and poverty as a whole by 70 percent.

“This gives us hope that something can be done, and we can increase the public will to make this happen,” she said.

Changing Communities

Dominic F. Gullo, a professor of early childhood education at Drexel University in Philadelphia said a significant investment in high quality early childhood education is also needed to help break the cycle of poverty.

“High quality early childhood education helps children maintain an advantage, and it has to go from birth to third grade,” Gullo explained. He pointed to research that says children impacted by poverty earlier in life suffer more from low birth rates, developmental delays than those who experience poverty later in life.

“With high quality early childhood education, from birth to third grade, students are less likely to drop out of school or become teen parents, and more likely to experience improved academic performance in language and math, as well as have higher attendance rates.”

New York State Alliance for Quality Education’s Zakiyah Ansari shared how a policy is placing 5,000 police officers in New York schools, costing $300 million. She questions why not social workers instead.

Another key element discussed during the symposium was to connect students to the community.

Wilson-Simmons of the National Center for Children in Poverty shared a project out of New York that connected middle school students with a college nursing program. Student nurses became mentors to the middle school students and would take them to local nursing homes to help.

“Students saw they had something to give,” said Wilson-Simmons, adding that her organization noted a significant decrease in the absentee rate. Many of the students who participated in this program ended up in health-based careers.

“When kids have a relationship to something beyond themselves it changes their perspective about themselves and what is possible,” emphasized Martin Blank, president of the Institute for Educational Leadership and director of the Coalition for Community Schools.

Some of the recommendations from the different groups included looking at the strengths of students living in poverty. A student may only have an 800-word vocabulary, but those are still 800 words that can be fully utilized. Develop strong relationships with families and students, and integrate wraparound services so students can feel socially safe.

Educators suggest to meet parents where they are. Host PTO meetings during a time when working parents can attend. Offer baby-sitting services. Spokane’s Chandler often finds herself washing students’ clothes and providing deodorant. Additionally, create a space that provide students with a better sense of identity and community.

With all the right mechanisms in place, students and their families can escape from the grips of poverty. Chandler of Rogers High School said, “We not only changed our school, we changed our community…and If you believe in us and in what we’ve done then you need to look differently about how schools are funded.” Four years ago, the graduation rate at Rogers stood at 46 percent. Today, it’s nearly 90 percent despite the area remaining impoverished.