When the Glendale Unified School District loosened cell phone use restrictions a few years ago, Chris Davis welcomed the change for two reasons. First, as a history and journalism teacher at Clark Magnet School, he looked forward to not spending an inordinate amount of his time chasing down wayward students with their ever-present smartphones.

“If the school tried to impose a ban, that’s how I would spend my day. What a waste of time and energy,” Davis says.

But Davis recognizes mobile devices as more than what some consider the “new chewing gum”—a nuisance more than an offense and one very difficult to enforce. He believes that as long as each of his students has access to a cell phone, and the parameters around their use are clearly defined, the classroom rewards outweigh the risks of a more open policy.

Sure, some students in other schools spend class time staring at their devices, texting, sharing, communicating through sites like Snapchat—generally presenting an ongoing classroom management provocation. But these are not major issues with Davis’ students. Accommodating cell phones in the classroom, he believes, doesn't amount to a deal with the devil.

Clark Magnet has a science and technology focus, which makes it ideally suited for a wider use of smartphone applications. But even in Davis’ history and journalism class, he encourages students to use the devices for oral histories. When using Google Docs/Drive, Davis finds that some students find typing and editing on a smartphone easier than the relatively bulky Chromebooks they also have access to in class.

“All the teachers are aware of the classroom management challenges, but it’s just a more realistic approach. When used carefully and with limitations, it is a very useful learning tool.”

Before New York City lifted its ban on cell phones in schools, many students had to pay a dollar to check their devices at a van before school. (AP Photo/Richard Drew)

Before New York City lifted its ban on cell phones in schools, many students had to pay a dollar to check their devices at a van before school. (AP Photo/Richard Drew)

Realistic. This is how many teachers describe their acceptance, if not embrace, of how the hyper-connected, media-saturated world of their students has gained a foothold in their classrooms. George Summerhill, a middle school teacher in Reno, Nev., calls it the “new reality,” one that he concedes he is ambivalent about. But Summerhill also doesn’t want to be trapped in what he views as myopic thinking about the looming dangers of classroom technology. Now in his 12th year of teaching at Cold Springs Middle School, Summerhill made adjustments, started small, and so far likes what he sees. He may sound a little resigned, but “cell phones aren’t going away so why not use them?” he asks. “Let’s turn it into a learning device and maybe eventually teens will see it more than just a device for entertainment.”

Julie Fleck, a science teacher at Mandan High School in North Dakota, doesn't see that evolution in her own students and believes the pedagogical rewards of cell phones in the classroom may be overhyped.

“Critical and creative thinking are key, and these devices in my opinion don’t really serve that goal,” says Fleck.

Still, according to a 2013 study by the Pew Research Center’s Internet and American Life Project, 73 percent of middle and high school classroom teachers use cell phones in their classroom instruction—a number that has likely increased over the past three years. So while it’s indisputable that educators’ comfort level and familiarity with these devices has increased, it's probably unwise to confuse their use with unbridled enthusiasm. Of those educators who integrate mobile devices in their instruction, many are keen to do so, but others fall into the grudging acceptance camp or somewhere in between.

Regardless of the level of enthusiasm (or complete lack of), the jury is still out about the long-term ramifications of, to use another popular platitude, “meeting students where they are.”

Even George Summerhill can’t help but wonder, “I’m not really sure what kind of Pandora’s Box we’ve opened up.”

Too Late to Turn Back?

While open cell phone policies are not the norm for most schools, the stigma around the devices has faded. More than 70 percent of school districts have taken their cell phones bans off the books (the most notable being New York City—the nation’s second largest school district, which did so in 2015.) This has resulted in a hodegpodge of guideline and rules. The decision about how to proceed—however cautiously—is often left up to individual teachers.

The rollback of cell phones bans, says Liz Kolb of the University of Michigan, has been driven to a large degree by parents—but not because they are clamoring for the devices to be used in classroom instruction.

“Unlike other technologies, there is something very specific about smartphones. It represents a life connected to entertainment, social media, gaming, and incessant texting” - Dr. Richard Freed

According to the Pew Center, some 88 percent of teens ages 13 to 17 have or have access to a mobile phone, and a 73 percent have smartphones.

“Students already had the devices and parents want to be able to connect with their children throughout the school day, thus some have pushed for a more inclusive policy,” explains Kolb. “Since students had the devices, schools began to think of ways they could utilize them in ways that made sense for classroom learning, rather than just seeing them as a distraction.”

Accordingly, many schools have adopted Bring Your Own Device (BYOD) policies that allow students to use their own cellphones in class under strict guidelines.

“While some teachers do bemoan BYOD policies, many have also embraced it, and looked for ways that the cell phones enhance and extend their learning goals in ways that they could not have done with traditional tools,” Kolb adds.

Steve Gardiner, a social studies teacher at Billings Senior High School in Billings, MT understands that in the hands of a well-trained first-rate teacher mobile technology has potential—in theory. The reality on the ground, he believes, is quite different.

“It’s just too tempting for a student. Once that phone is brought out, most can’t resist texting a friend or begin playing a game right in the middle of a lesson,” Gardiner says. “In all my years of teaching, cell phones have been by far the most distracting presence.”

Cell Phones in the Classroom: Understanding the Long-Term Consequences

Gardiner, the 2008 Montana Teacher of the Year, doesn’t necessarily doubt that mobile devices in the classroom foster greater student “engagement,” but does engagement automatically lead to learning? “I think these devices fragment students’ thinking,” he says.

And what does the research say about learning? What’s available, which isn’t an abundance, presents a murky picture. A 2014 study by Stanford University found positive effects for digital learning on lower-achieving students but didn’t specifically focus on smartphones. On the other hand, a study released in May 2016 by the London School of Economics looked at 91 schools in four U.K. cites and found that the schools that banned cell phones had higher test scores—particularly among low-achieving students.

Steve Gardiner

Steve Gardiner

The debate over cell phones in school, however, extends beyond the parameters of pedagogical appropriateness and classroom management. Concerns about cell phones in the classroom are also grounded in what we know about teenage brains, including the inability to concentrate while multitasking and possibly long-term effects on overall health.

Dr. Richard Freed, a a child and adolescent psychologist says it is past time to start calling teenagers’ attachments to these devices—or more accurately their applications—what it is: addiction.

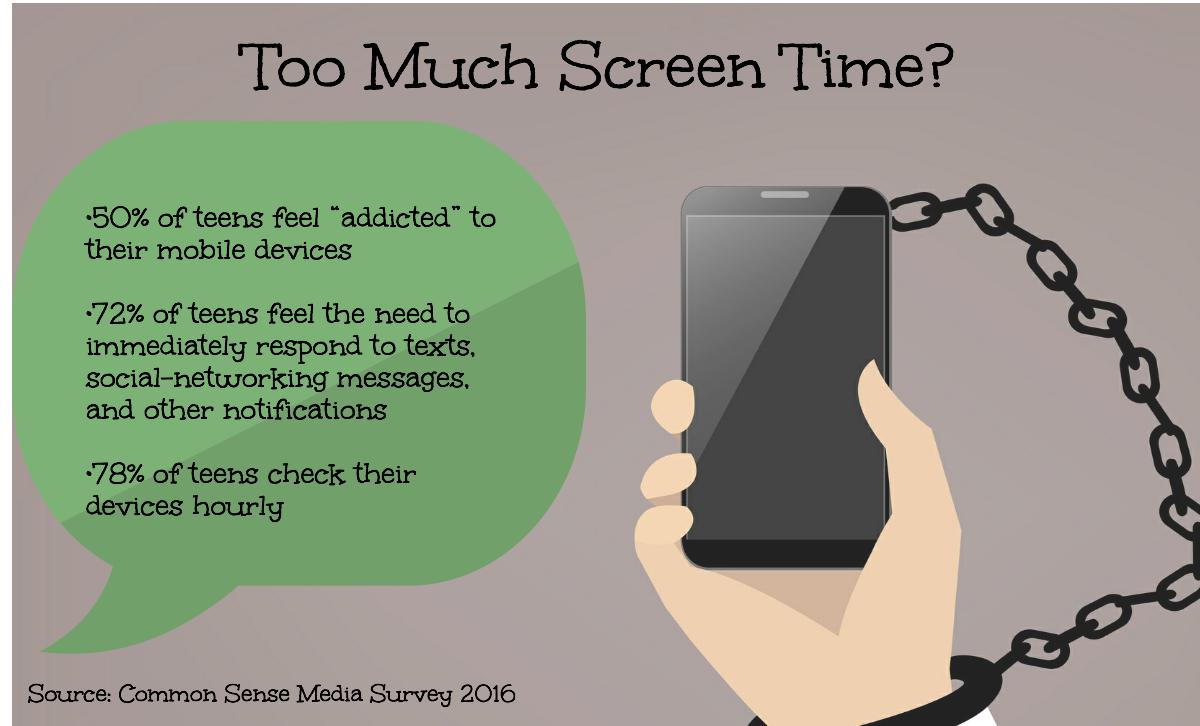

“Unlike other technologies, there is something very specific about smartphones. It represents a life connected to entertainment, social media, gaming, and incessant texting,” Freed says. A 2016 survey from Common Sense Media, involving 1,240 interviews with parents and their 12- to 18-year-old children, revealed that 50 percent of teens do feel “addicted” to their mobile devices.

“We’ve had to psychiatrically hospitalize kids when parents try to set limits on phones or take them away. Police are sometimes called. Teachers are confronting the same thing in schools every day,” says Freed.

As the conversation broadens to incorporate issues like brain development and addiction, finding that middle ground on cell phones in the classroom could be even more elusive. Can we adapt our classrooms to the connected world of students while avoiding the consequences that have yet to be fully identified and understood?

There’s no doubt many educators are successfully integrating cell phones in their instruction and doing so in moderation, but Steve Gardiner wonders if we’re just feeding the beast.

“Addiction is a strong word, but I think it’s accurate,” Gardiner says. “I know how much time I’ve spent dealing with cell phones. When I think about the accumulative effect in classrooms across the nation - the time lost we should be spending on instruction and building student relationships, I realize how much this one problem has cost us.”