This article was updated in March 2019.

Even the 4- and 5-year-olds in Marty Davis’ Utah kindergarten classroom get anxious. “We expect so much from them, and they feel the pressure,” she said. “They’re like ‘I can’t!’ And I’m like [the Little Engine That Could, who says], ‘I think I can! I think I can! I think I can!’”

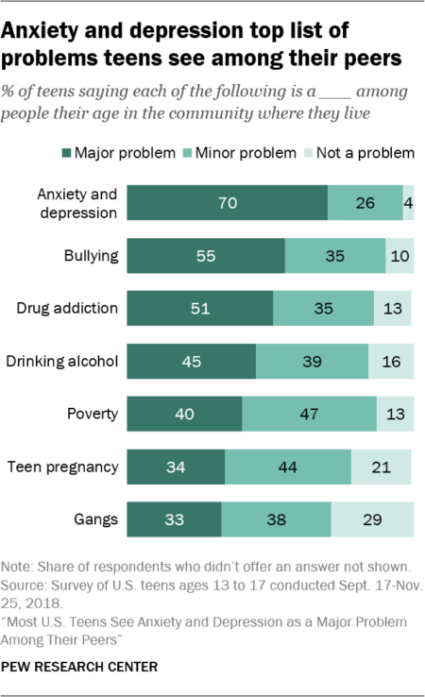

By high school and college, many students have run out of steam. Anxiety—the mental-health tsunami of their generation—has caught up with them. Today’s teens and young adults are the most anxious ever, according to mental-health surveys. They admit it themselves: In February, a Pew survey found that 70 percent of teens say anxiety and depression is a "major problem" among their peers, and an additional 26 percent say it's a minor problem.

“Honestly, I’ve had more students this year hospitalized for anxiety, depression, and other mental-health issues than ever,” said Kathy Reamy, school counselor at La Plata High School in southern Maryland and chair of the NEA School Counselor Caucus. “There’s just so much going on in this day and age, the pressures to fit in, the pressure to achieve, the pressure of social media. And then you couple that with the fact that kids can’t even feel safe in their schools—they worry genuinely about getting shot—and it all makes it so much harder to be a teenager.”

In 2016, nearly two-thirds of college students reported “overwhelming anxiety,” up from 50 percent just five years earlier, according to the National College Health Assessment. For seven straight years it has been the top complaint among college students seeking mental-health services, notes the Chronicle of Higher Education. Nearly a quarter say their anxiety affects their academic performance. Common symptoms include persistent feelings of dread and jumpiness, frequent panic attacks, as well as headaches, stomach problems, shortness of breath, and fatigue.

Reamy does all that she can to talk to students about deep breathing exercises, the power of positive self-talk, healthy nutrition, yoga, sleep, and more. She hands out stress balls, and encourages therapy. Together, she and her anxious students sit and unravel the things that are making them anxious. They talk about ways to cope in the short term and to resolve the issue in the long term. She points out that their typical tactics—teens “tend to self-medicate with drugs and alcohol”—only make things worse.

But, with more than 325 students in her charge and acres of paperwork to complete each week, Reamy has limited time. Most of her peers have even less time. Even as the mental health issues worsen each year, the national average is 491 students per counselor. Only three states in the nation meet the overall recommended ratio of 250-to-1 for students-to-school-counselor.

Have Smartphones Made Student Anxiety Worse?

Experts point to a number of reasons that anxiety has blossomed among today’s students. “I see two major issues,” says Rob Benner, a Bridgeport, Conn., school psychologist with nearly 30 years’ experience. “One is testing anxiety, and the other is anxiety over social media.”

Today’s teenagers grew up in classrooms governed by No Child Left Behind, the federal law that introduced high-stakes standardized testing to every public school in America. In kindergarten, instead of making art and new friends, they learned to write full-on sentences in timed tests. Hours spent in art, music, physical education and recess were limited, or eliminated. For fun, these students attended pep rallies to pump them up for state testing.

Honestly, I’ve had more students this year hospitalized for anxiety, depression, and other mental-health issues than ever. There’s just so much going on in this day and age, the pressures to fit in, the pressure to achieve, the pressure of social media." - Kathy Reamy, school counselor

By high school, high-achieving students face overwhelming pressure to succeed—and their parents aren’t always helpful. “They have start taking the SATs in eighth grade,” says Reamy. “It’s so hard for the kids who are already maybe perfectionists, and they’re getting the first B in their lives and they’re fearful it’s going to prevent them going to college, any college, never mind their dream college. And they don’t want to disappoint their parents.”

In the Pew survey of teens, academic pressure tops their list of stressors: 61 percent say they face a lot of pressure to get good grades. By comparison, 29 percent say they feel pressure to look good; 28 percent to fit in socially; and just 6 percent to drink alcohol.

The other issue is social media. A study published in Clinical Psychological Science points to the development of something very troubling in the lives of U.S. teens between 2010 and 2015. During those five years, the number of teens who felt “useless and joyless” surged 33 percent. The number of 13- to 18-year-olds who committed suicide jumped 31 percent.

“What happened so that so many more teens, in such a short time, would feel depressed, attempt suicide and commit suicide?” wrote one of the study’s authors, San Diego State University professor Jean Twenge, in a Washington Post column. “After scouring several large surveys for clues, I found that all of the possibilities traced back to a major change in teens’ lives: the sudden ascendance of the smartphone.”

Teens who spend five or more hours online a day were 71 percent more likely than those who spent only one hour a day to have at least one suicide risk factor, Twenge’s research found.

“I have one student who is completely addicted to social media and her phone,” said Reamy. “It was honestly preventing her from doing what she needed to do at school. So, now she leaves her phone in my office. She still comes between classes to check some things, and she’s got it for a solid hour at lunchtime. For her, it’s like an appendage, like her right arm!”

Students are incredibly mean to each other on social media. They say things to a screen that they would never say face to face, things like “you should kill yourself.” And many studies have found that increased social media use actually makes people feel more socially isolated. It also disrupts sleep, which is related to mental health.

Schools can create policies around phone use during school hours, but ultimately “parents need to manage the time that students are on their phone, and I think students need to earn that time,” said Brenner.

Solutions are complex, advocates say. Reamy often suggests therapy to students and parents, but many are resistant. School psychologists and counselors need more time to spend with one-on-one with students, but that’s difficult to find in these days of austerity. Many school districts, alarmed by rising suicide rates, are hosting community-wide conversations, involving students, parents, and educators, about the academic and social pressures placed on kids.

“Despite the fact I go to high school every day, I often say, ‘I would not want to go back to high school,’” said Reamy. “People don’t understand how hard it is to be a kid today.”